Key Facts

- MRKH is a disorder of the female reproductive tract–approximately 1 in 5,000 females are born with it.

- Girls are often diagnosed between the ages of 15-18 when they don’t get a period.

- Treatment options may include dilation, surgery, or a combination of both.

You may have just learned that you have MRKH (Mayer Rokitansky Kuster Hauser Syndrome). You’re probably thinking, “Why is the name so long?” It’s extra-long because this condition is named after all of the doctors who discovered it. Aside from being overwhelmed with the name of this condition, it’s also normal to feel confused, scared, and sad about having MRKH. It’s also perfectly fine if you simply feel relieved to know why you don’t have periods. Most likely you and your parents have a lot of questions. We hope that this guide will help answer your concerns. We also have a special guide for your parents.

What is MRKH?

MRKH is a congenital disorder that affects the female reproductive tract. Congenital means that it’s acquired during development and present at birth. About 1 in every 5,000 female babies has this condition. MRKH is a syndrome (group of symptoms). We don’t know the cause of this syndrome, but we do know that when a baby grows in their mother’s uterus (womb), organs and systems develop. One of the systems is called the reproductive system, which in female babies includes the uterus, cervix, vagina, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. The reproductive system is formed during the first few months of “fetal” life (while a baby is still in her mother’s womb). With MRKH, the reproductive system starts to grow but doesn’t completely develop.

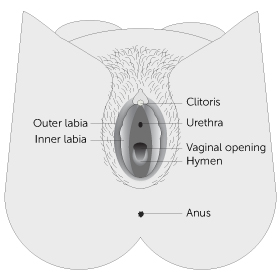

Girls with MRKH have normal ovaries and fallopian tubes. Most often the uterus is absent or tiny. The vaginal canal is typically shorter and narrower than usual or it may be absent. Sometimes, there may be one kidney instead of two. About 3% of girls diagnosed with MRKH will have a minor hearing loss and some may have spinal problems such as scoliosis (curvature of the spine). Girls with MRKH have “normal external genitalia,” which means that everything on the outside of the vagina is not affected. This part of your body is called the “vulva” and includes what you can see – clitoris, urethra, labia, vaginal opening, hymen, and anus.

When is MRKH diagnosed?

The most common age for MRKH to be diagnosed is when a young woman is between 15 and 18 years old. That’s when a young woman is likely to see her health care provider because she hasn’t started her period. Some girls may find out at an earlier age or when they’re older.

What will happen at my doctor’s appointment?

Your doctor will probably ask you questions such as: “When did you notice that your body was changing… going through puberty?” Next, your doctor may want to take a look at your outer female organs and also check to see how long your vagina is. Your doctor will gently put a Q-tip or gloved pinky finger at the opening of your vagina and then very slowly and carefully place the tip into the vagina to see how deep it is. If your doctor thinks you might have MRKH, they will probably order a test called an ultrasound or an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). These tests do not hurt and are similar to having an x-ray. Usually your doctor will refer you to a specialist who has experience taking care of young women with MRKH. A pediatric/adolescent gynecologist is a doctor with special training in young women’s reproductive health.

What can a pelvic ultrasound or MRI show?

A pelvic ultrasound is usually the first test to check to see if a uterus or womb is present. This test can also confirm that you have two ovaries and two kidneys. Sometimes a very tiny uterus can be seen. A tiny uterus is called a “uterine horn or remnant”. You may need to have an MRI so that your doctor can see your female organs in more detail.

Can anyone tell that I have MRKH (besides my doctor)?

Some young women wonder if anyone can tell if they have MRKH. The answer is no. No one, except you and your gynecologist, can tell that you were born with an incomplete vagina and following treatment, with dilators or surgery, your sexual partner will not be able to feel any difference.

Will I be able to have children?

If you were born with an incomplete vagina but have a normal size uterus, it is likely that you will be able to become pregnant and carry a baby. If you were born without a uterus or if your uterus is tiny, you will not be able to carry a pregnancy. Since you have ovaries and make eggs, one of your eggs can be fertilized with your partner’s or a donor’s sperm. Adoption is another choice for some couples.

Surrogacy: Someone else such as your sister, friend, or another person you choose, could potentially be a gestational carrier. Gestational carriers are women who agree to carry a pregnancy for a couple. Because this child would be created using your egg and your partner’s or a donor’s sperm, you would be the biological parent of this child.

Uterine transplants: This is a very complicated surgery that was first performed in Sweden in 2014. The process involves finding a major health care facility that is conducting a clinical trial, then applying to be in the program. Next steps include: IVF procedure where an egg and sperm are harvested and embryos are created and frozen for later use in a transplanted uterus [or gestational carrier], finding a uterine donor or using a deceased uterus, who is a match, having surgery (donor and recipient), waiting up to a year then having an embryo is then placed in the transplanted uterus. Immunosuppressive drugs must be taken by the recipient for the duration (while she has the transplanted uterus). If all goes well and a healthy pregnancy happens, the baby is delivered by C-section. At this time, a uterine transplant is “temporary”. After the baby is delivered, the recipient has the option to maintain the uterus for a 2nd child and then the donated uterus is removed. To date, there have been sixteen babies born to women who have undergone a uterine transplant in Sweden. The first uterine transplant in the U.S. took place in February 2016 and the first baby born after a successful uterine transplant was in 2017 at the Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, TX. Recently there has also been a successful live birth in the USA after transplant from a deceased donor. Uterine transplant surgery for absolute uterine factor infertility (AUI) is considered an option that is highly experimental and not all of the risks are well known. However, the procedure offers hope for women who aren’t otherwise able to carry a pregnancy.

Science is always moving forward and fertility options are improving every day. By the time you are ready to have children, there may be more options available to you.

Why might I have pelvic (belly) pain each month?

In general, some women can tell when they ovulate (make an egg) each month because they feel some discomfort or twinge in their lower belly. Most of the time this mild pain is nothing to worry about as it is caused from normal ovulation. Some women with MRKH may have a tiny uterus called a “uterine remnant” or “uterine horn.” This type of uterus or womb is not big enough to carry a baby but sometimes it can cause pelvic pain if blood leaks into the pelvic cavity. Your gynecologist will be able to tell if you have a small uterus and if it needs to be removed. If you have belly pain, it’s important to tell your medical team.

If I don’t create a vagina but I do decide to have sex, will anything bad happen?

If you have vaginal intercourse before your vagina is created using dilators or surgery, sex will likely be very painful. It could cause a tear in your vagina and bleeding. Creating a vagina with vaginal intercourse alone can be done but comes with risks and is usually very uncomfortable. However, there are other ways in which couples can be sexually intimate that do not involve vaginal penetration. When you are ready to become sexually active, having MRKH will not limit your ability to engage in other sexual activities, nor will it limit your ability to experience sexual pleasure.

Will I ever be able to have a satisfying sex life?

YES. Keep in mind that every woman, regardless of her age or health issues experiences sexual stimulation and pleasure in different ways. Discovering what you enjoy sexually is an evolving process throughout your life. Thus, women with MRKH who are sexually active are encouraged to explore their sexuality with themselves and with their partner(s) to learn what feels both comfortable and pleasurable.

I’m in boarding school/college and have a roommate – How do I get some privacy to use the dilators?

Most young women find that they need privacy when using the dilators. When you are sharing a room, either with a sibling or roommate, it can be uncomfortable asking for time alone, especially if you don’t want to share any details of your diagnosis or treatment.

There are many reasons why people need to have some time alone: meditating, studying, napping, praying, etc. It’s always best to plan ahead, so check with your roommate to find out when she will be in class or out of your dorm room so you’ll know when you will have private time to use your dilator.

I’m really embarrassed with all the medical visits – will this ever get easier?

Many young women diagnosed with MRKH feel pushed into a world of new information and new experiences. It’s perfectly normal to have a range of emotions: sadness and anger, hope and worry, fear and embarrassment can all be part of the experience. Your medical team: your gynecologist, nurses, and social worker, are aware of these feelings and they are trained to be sensitive to your unique situation. You may be the kind of person who wants a lot of interaction and information at all the visits or you may be someone who just wants the facts and prefers to keep the visits as brief as possible. One thing that you can do to make this process easier is to tell your medical team what approach would be most comfortable for you during your follow-up appointments. The team will do their best to make sure your appointments are as stress-free as possible.

My parents want to keep talking to me about MRKH but I already feel like my privacy has been taken away – how do I keep some boundaries?

An essential part of growing up is becoming more independent as well as setting some boundaries between you and your parents. When there is a medical issue that requires many appointments and exams, it can be hard to feel a sense of privacy. Additionally, since MRKH by definition involves both you and your parents thinking of you as a sexual person, the stress level in families may be very high at first. For many young women and their parents, the conversations you have been having about your body may feel uncomfortable or like an invasion of your privacy.

At the same time, just as you have had to get used to this diagnosis and what it all means, so do your parents. They are likely worried about you and how you are coping with this new information, and many parents show this by asking a lot of questions about how you’re doing. It is important for you to be honest with your parents about what you need, including respectfully letting them know when you don’t feel like talking. Your parents may find it helpful to talk to other family members like an aunt or a grandparent, but you should be included in conversations about who will be told about your diagnosis.

Your parents may also find it helpful to read the Parent’s Guide to MRKH, which answers the most frequently asked questions parents have.

You can also talk with members of your medical team for help with communicating with your parents.

Is there anyone else I can talk to about having MRKH?

Some young women find it helpful to talk with a parent(s) or other family members, while other girls prefer to talk with a counselor or a close friend. We know that it can be very helpful to talk with someone your own age that has MRKH. The Center for Young Women’s Health at Boston Children’s Hospital offers free bi-monthly online chats for young women with MRKH and a yearly conference for teens/young women diagnosed with MRKH and their families. Your medical team may also be able to connect you with another young woman with MRKH, or help you find a counselor if this is something that you are interested in pursuing.

Am I still a biological woman?

It’s not uncommon for young woman to wonder if they are “really a girl” when they first learn that they are born with an incomplete vagina and uterus. If you have asked yourself this question, you are not alone. However, it’s very important for you to understand that you are a female. Your doctor may order a special blood test that can confirm that you are a genetic female and have 46XX chromosomes.

Will my vagina ever close up?

Once you have created a vagina your vagina shouldn’t change or shrink if you are having vaginal intercourse or using the dilator about once a week. If you are not sexually active, you should use the largest size dilator once a week for about 20 minutes (only after you are finished creating your vagina).

I don’t want to use the dilators now – can I wait until I feel ready? What happens if I never create a vagina?

The choice whether to have treatment – as well as how and when – IS UP TO YOU! Like any important decision, it is essential that you get all the information before you make the decision to have treatment. Talking with other women who have MRKH is valuable too. You are in control of your body. You should never be forced or pressured into having treatment by your parents, partner or medical team. Rather, they should support you during the treatment process only when you decide the time is right. Your medical team has the responsibility of giving you information and resources to help you understand your reproductive health issues so YOU can make informed decisions. Your parents have the responsibility of helping you get medical care and helping you obtain privacy at home if/when you choose to use dilators. You have the responsibility to learn more about MRKH and to talk with a trusted adult if you are feeling overwhelmed.

Our health guides are developed through a systematic, rigorous process to ensure accuracy, reliability, and trustworthiness. Written and reviewed by experienced healthcare clinicians from Boston Children's Hospital, a Harvard Medical School teaching hospital and consistently ranked as a top hospital by Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report, these guides combine clinical expertise, specialized knowledge, and evidence-based medicine. We also incorporate research and best practices from authoritative sources such as the CDC, NIH, PubMed, top medical journals, and UpToDate.com. Clinical specialists and subject matter experts review and edit each guide, reinforcing our commitment to high-quality, factual, scientifically accurate health information for young people.